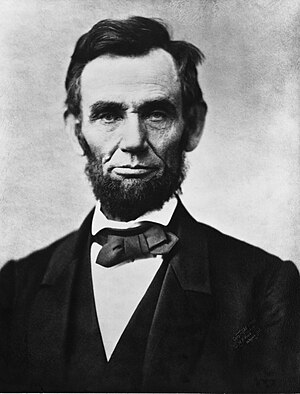

Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia John Beauchamp Jones

FEBRUARY 13TH.--Coldest morning of the winter.

My exposure to the cold wind yesterday, when returning from the department, caused an attack of indigestion, and I have suffered much this morning from disordered stomach and bowels.

From Northern papers we learn that Gen. Grant's demonstration last week was a very formidable effort to reach the South Side Railroad, and was, as yet, a decided failure. It seems that his spies informed him that Gen. Lee was evacuating Richmond, and under the supposition of Lee's great weakness, and of great consequent demoralization in the army, the Federal general was induced to make an attempt to intercept what he supposed might be a retreat of the Confederate army. There will be more fighting yet before Richmond is abandoned, probably such a carnival of blood as will make the world start in horror.

The New York Tribune still affects to believe that good results may come from the recent peace conference, on the basis of reunion, other basis being out of the question. The new amnesty which it was said President Lincoln intended to proclaim has not appeared, at least our papers make no mention of it.

Gen. Lee has proclaimed a pardon for all soldiers, now absent without leave, who report for duty within 20 days, and he appeals to their patriotism. I copy it.

My exposure to the cold wind yesterday, when returning from the department, caused an attack of indigestion, and I have suffered much this morning from disordered stomach and bowels.

From Northern papers we learn that Gen. Grant's demonstration last week was a very formidable effort to reach the South Side Railroad, and was, as yet, a decided failure. It seems that his spies informed him that Gen. Lee was evacuating Richmond, and under the supposition of Lee's great weakness, and of great consequent demoralization in the army, the Federal general was induced to make an attempt to intercept what he supposed might be a retreat of the Confederate army. There will be more fighting yet before Richmond is abandoned, probably such a carnival of blood as will make the world start in horror.

The New York Tribune still affects to believe that good results may come from the recent peace conference, on the basis of reunion, other basis being out of the question. The new amnesty which it was said President Lincoln intended to proclaim has not appeared, at least our papers make no mention of it.

Gen. Lee has proclaimed a pardon for all soldiers, now absent without leave, who report for duty within 20 days, and he appeals to their patriotism. I copy it.

HEADQUARTERS ARMIES OF THE CONFEDERATE STATES,

February 11th, 1865.

GENERAL ORDERS NO. 2.

In entering upon the campaign about to open, the general-in-chief feels assured that the soldiers who have so long and so nobly borne the hardships and dangers of the war require no exhortation to respond to the calls of honor and duty.

With the liberty transmitted by their forefathers they have inherited the spirit to defend it.

The choice between war and abject submission is before them.

To such a proposal brave men, with arms in their hands, can have but one answer.

They cannot barter manhood for peace, nor the right of self-government for life or property.

But justice to them requires a sterner admonition to those who have abandoned their comrades in the hour of peril.

A last opportunity is offered them to wipe out the disgrace and escape the punishment of their crimes.

By authority of the President of the Confederate States, a pardon is announced to such deserters and men improperly absent as shall return to the commands to which they belong within the shortest possible time, not exceeding twenty days from the publication of this order, at the headquarters of the department in which they may be.

Those who may be prevented by interruption of communications, may report within the time specified to the nearest enrolling officer, or other officer on duty, to be forwarded as soon as practicable; and upon presenting a certificate from such officer, showing compliance with this requirement, will receive the pardon hereby offered.

Those who have deserted to the service of the enemy, or who have deserted after having been once pardoned for the same offense, and those who shall desert, or absent themselves without authority, after the publication of this order, are excluded from its benefits. Nor does the offer of pardon extend to other offenses than desertion and absence without permission.

By the same authority, it is also declared that no general amnesty will again be granted, and those who refuse to accept the pardon now offered, or who shall hereafter desert or absent themselves without leave, shall suffer such punishment as the courts may impose, and no application for clemency will be entertained.

Taking new resolution from the fate which our enemies intend for us, let every man devote all his energies to the common defense.

Our resources, wisely and vigorously employed, are ample, and with a brave army, sustained by a determined and united people, success, with God's assistance, cannot be doubtful.

The advantages of the enemy will have but little value if we do not permit them to impair our resolution. Let us, then, oppose constancy to adversity, fortitude to suffering, and courage to danger, with the firm assurance that He who gave freedom to our fathers will bless the efforts of their children to preserve it.

R. E. LEE, General."

The Senate did nothing on Saturday but discuss the policy of abolishing the Bureau of Conscription, the office of provost marshal outside of our military lines.

Gov. Smith's salary is to be increased to $20,000, and he is still exempting young justices, deputy sheriffs, deputy clerks, constables, etc.